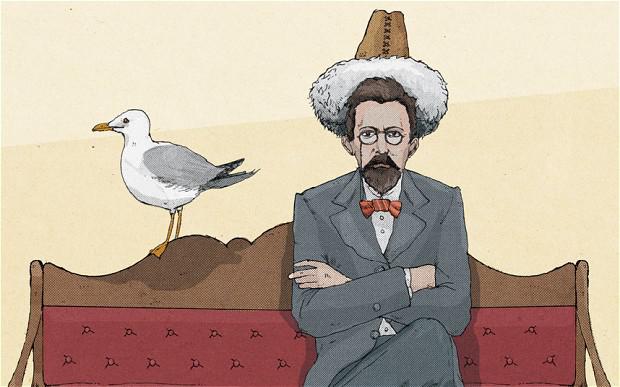

Anton Chekhov, trip to Sakhalin Island (Approach I)

Discover Chekhov

The most normal thing is that the new reader of Anton Chekhov (January 29, 1860 -Taganrog, Russia-; July 15, 1904 -Badenweiler, Baden, Germany), widely spread, read his stories first. I consider myself lucky to have known his theater before. It was a cold and dramatic shock, modern, contemporary and classic, distant but intimate, poetic, to read La gaviota as a university theater student, in the version published by UNAM in 1983 (second reprint), originally released in 1973; translation by Lydia Kuper, from 1946. The impact was brutal but artistic or artistic but brutal. Overwhelming. Once and forever. Then followed, The Cherry Orchard, The Lady with the Dog and many short stories and novellas; essentially, in editions of Porrúa.

And it was impressive both on the intelligence side and on the sensitive side, since I was part of the theater workshop of the Faculty of Political and Social Sciences, and sensitivity and reason (in that order) made their way under the teaching and guidance of Ramiro García, actor graduated from the University Theater Center (surprising at the time for having replaced an undisciplined Juan José Gurrola in Martirio de Morelos, by Vicente Leñero, directed by Luis de Tavira at the Juan Ruiz de Alarcón Theater of the University Cultural Center) , who trained us at the school of Konstantin Stanislavski, founder of the Moscow Art Theater in 1897 together with Vladímir Ivánovich Nemiróvich-Dánchenko, a space in which Chekhov would find the “natural” place for his breakthrough dramaturgy. And also love, since he would be the partner and husband of Olga Knipper, one of the main actresses of the group that in fact re-released The Seagull in the starring role of Arkádina. His genius would join them, not without controversy, before the approaches of the leaders of the theater group.

While taking part in the workshop and participating in the staging of Esperando al zurdo, by Clifford Odets, An Enemy of the People, by Henri Ibsen, and La Atlántida, by Óscar Villegas, among others, I read Chekhov with emotion. And one day the desire arose to know more about the author , the character, the man, the human being who died young, of tuberculosis at the age of 44; cruel death, unjust for a genius, painful, if it is allowed to say (Mozart, Pushkin, Revolts…; how many young deaths!).

Today's most read columns

structure of his work

A. Although in my case the first impact was as a result of his theater , in chronological terms Chekhov's work is structured first by the short story. Almost at the same time, he began to develop an equally short and humorous early theater –according to Vladimir Nabokov, “what he wrote the most were small humorous pictures that he signed with different pseudonyms, reserving his real signature for articles on medicine ”; he signed above all as Antosha Chejonté-, experimental works in one act; such as On the damage caused by tobacco, from 1886 (which he would revise towards his death), an echo of the plays he wrote as a teenager to stage with his brothers. For her part, Natalia Ginzburg points out that the stories commissioned as early as the autumn of 1882 by the humorous magazine Astillas, “had to be brief, light and comic, take censorship into account and avoid any reference to the harshness of the times”; they contained illustrations of his brother Nikolai. A magnificent example is "Horse Surname", from 1885.

Chéjov would earn 8 kopecks per line – he had gone from five in La Libélula to six in El Desperdordor and El Espectador, and would later reach 12 in Tiempo Nuevo, by Aleksei Suvorin, his main editor in the future-, but he made NA Leikin, director of the St. Petersburg magazine, two petitions, records Ginzburg; He “to be able to write longer stories, which she was allowed, and to be able to write a story that was not funny, which she was also allowed to do. Leikin expressed some doubts. However, the readers loved these stories and, however they were, they received them with joy. In this way, Chekhov finally had the power to combine, on some occasions, humor with melancholy, and to features that provoked smiles, add emotion, pity and pain. Since he began to write, he was finally free to abandon the only source from which he had been allowed to draw, comic humor, as well as the limited and schematic view of existence. Now, if in comic stories laughter was born along with a cold shudder, in more serious stories emotion and pain were born from an inclement and cold atmosphere, which took one's breath away, like the air when it snows. And if the reader shed a tear or two, the writer was always dry-eyed. In addition, the characters in his stories endlessly offered comments, judgments, observations, opinions. The writer offered no comment. He did not agree with anyone or take it away. This is how Chekhov was in the first accounts of him and this is how it was in the last ones. A writer who never commented.”

B. Then comes the short novel or long story ; it depends on the interpretation. For example, Story of my life, Room number six, In the ravine, Peasants, A boring story or The Steppe.

Later , the great theater with a body of five outstanding works and an important antecedent, Ivanov (1887; it was performed at the Korsh Theater in Moscow in November of that year and until 1889 with great success in Saint Petersburg), which prefigures to The Seagull and His Spirit (premiered as a flop in 1896 and re-released by Stanislavski in 1898 with resounding and transcendent success), and what would come from it, Uncle Vanya (1899; released in 1900, also directed by Stanislavski; actually , it was the rewriting of The Spirit of the Woods, written in the autumn of 1899 and premiered at the Abramov Theater in Moscow without success), The Three Sisters (1900), and the last play, The Cherry Orchard (1904 ); already in full glory of a dying author. An originally untitled play made up of four acts, dated 1880, was found in its original version (the author had destroyed it), and published in 1923, it would perhaps be Chekhov's first "serious" but unsuccessful theatrical attempt in the midst of the short stories and short drama as well; he is currently known as Platonov.

D. That literary body was enriched after Chekhov's death by his correspondence with various characters such as his girlfriend and wife Olga Knipper (1899-1904), Leo Tolstoy, Maxim Gorky, his brothers, his publisher Suvorin, among others.

E. Sakhalin Island is a separate chapter. The result of his trip in 1890 to that remote geography, an empirical, scientific essay, but without a doubt with hints of the author's literary encouragement. When his publisher decided to incorporate it into the publication of his complete work, Chekhov turned it down; he was convinced, but demanded that it be published in a separate volume.

Studies and references

During my university years, I only had access to studies published in Mexico about Chekhov and his work. Prologues, introductory texts, notes and presentations of works. Currently, in addition to literary studies, there is material on the internet, articles, short essays, conferences and readings. Among the "Mexican" material available from the 70's of the XX, I cite the following:

Michael Guard. Prologue to The Seagull and The Cherry Orchard; UNAM, 1983 (first edition, 1973); translation by Lydia Kuper, Foreign Languages Editions, USSR, 1946.

Juan Lopez-Morillas. Preliminary Note (and translator) to Ivánov, La gaviota and Tío Vania; Editorial Alliance, 1990, edition taken from the complete works of Chekhov, Moscow, 1960-1964.

Marc Slonim. Prologue to short novels of Chekhov, published by Porrúa, 1999 (first edition, 1993).

Rafael David Juarez Onate. Prologue to Tales, by Chekhov; United Mexican Publishers, 1999.

Somerset Maugham. Prologue to Selected Tales of Chévoj, published by Porrúa in 1983. Magnificent original essay from 1939.

To the above, we must add the work and perspectives of Natalia Ginzburg, Irène Némirovsky, Enrique Salgado Gómez, Donald Rayfield, Harold Bloom, Kazimierz Waliszewski, among others. And in particular, to Vladimir Nabokov, in his capacity as a great critic of Russian literature also fueled by the breath of creation (although he had to wait until 1958 for the triumph of Lolita). And to ratify a phrase that one has arrived at even before reading the author of Lolita: “Chekhov is, along with Pushkin, the purest writer Russia has given, in the sense of the complete harmony that his writings communicate about him ” .

Nabokov's contribution with his Course on Russian Literature (1981; translation by María Luisa Balseiro and edition by Fredson Bowers), in which he analyzes Gogol, Turguéniev, Dostoevsky, Tolstoy, Chekhov and Gorki, is essential. It is about the meeting and reconstruction of the classes taught at Wellesley College and Cornell University, in the United States, from 1941 and 1948, respectively. Its procedure is simple: it offers biographical elements of the particular author in question and later analyzes some selected or preferred works. Nabokov affirms that already in 1940, before beginning his academic life in the United States, he had written about a hundred lectures, approximately 2,000,000 pages on Russian literature, which served as the basis for his teaching and, later, for the formation of the great book aforementioned critic.

In the case of Chekhov, the synthetic, specific and clear biographical sketch that he offers is very relevant - even more praiseworthy than the particular analysis of the chosen works: The Lady with the Dog, In the Ravine and The Seagull -, because he was one of the early scholars of the character; along with Somerset Maugham and Natalia Ginzburg. From them, Chekhov's biographical itinerary can be established without doubt and loss, especially in what corresponds to the years prior to literary success. From this, Nabokov is blunt, since he points out about the first two collections, Miscellaneous Tales and At Twilight, which appeared in 1886 and 1887: “they were immediately acclaimed by the public. From then on he was counted among the first-rate writers, he was able to publish his stories in the best magazines, and abandon his medical career to devote all his time to literature”. It is when Chekhov begins to conquer Olympus in that flashback arc that travels from him to Alexander Pushkin. A period of barely 80 years of glory for Russian and universal letters.

Finally and recently (as far as this text is concerned), Víctor Gallego Ballestero makes an important contribution with the translation and the introductory study to La Isla de Sajalín; Titivillus Digital Publisher, 02-03-16. For the translation, the edition of Complete Works in eighteen volumes published in Moscow by the Nauka publishing house in 1987 was used, which reproduces the text of the 1902 edition of AF Marx, established and revised by the author. Original title, Ostrov Sakhalin.

Undoubtedly, the edition of Chekhov's “complete works” in Spain has good introductory studies; although not exhaustive, because the important thing is the work. Complete works endorsed by the author being aware, as a doctor, of the brevity of his existence, yes, but also by the successful and famous writer that he was and could afford that luxury just after 40 years of age.

Sakhalin Island

“On July 5, 1890, I arrived by ship at the city of Nikolaevsk” (in the extreme east of Russia), Anton Chekhov points out in The Island of Sakhalin (where he would set foot on land on the 11th), a kind of chronicle crossed by the objective gaze and the practical empirical of the doctor, of the scientist and the pen not of the globetrotter but of the one who embraces an almost fantastic adventure and records it; almost because, despite being extraordinary, it is real, authentic. And despite the nature of his genre, the beautiful glimpses of the poet he has become at the age of thirty do not cease to appear here and there. Work that he, by the way, thought of as a means to become a doctor, but was rejected. And he wanted to leave it out of the complete works referred to, considering it a non-literary product, but he gave in to the editor's insistence.

He had just turned 30 years old, on January 29, 1890, when Chekhov, despite family pleas, medical warnings and advice from his publisher friend Aleksei Suvorin, set out on April 21, the enormous journey of ten thousand kilometers from Moscow to Sakhalin, an island in the process of being colonized by prisoners; an isolated penal colony. Location: Sea of Okhotsk in the Pacific; to the south, Hokkaidō, Japan, separated by the Strait of La Pérouse, and from Siberia by the Strait of Tartary. The writer himself organized his road map.

At a time when the Trans-Siberian railway did not yet exist (completed the year of his death in 1904), the 82-day journey was made by steamboat, carriage and even three tens of kilometers on foot. Until then, the island had been a geography of struggle in historical dispute over China, Korea, Japan and Russia; it would remain in its possession at the end of World War II. Nikolaevsk was at that time the point of arrival of the main steamers in circulation. From there, which Chekhov takes as the starting point for his work, he will go to the four corners of the island to observe, study and record life on it.

Having lived only 44 years and with a successful work in the story and drama, the existence of that extensive work of sociological, anthropological and empirical research that is The Island of Sakhalin , appeared as a complete work in 1894, was almost always ignored or disdained. but whose chapters were published in installments. And I have for me that from that trip (whose consequence is the book), there is a rupture or a rupture is confirmed in the life of the author. A before and after highlighted by her tuberculosis attacks at 24 and 27 years of age (at fifteen she was about to die of peritonitis), and the recent death of her brother Nikolai in June 1889. If she was always human, his sensitivity deepens as he witnesses the misfortunes and miseries of the inhabitants of Sakhalin. And how could such an undertaking, so cyclopean, not be a breach! That watershed is naturally manifested in the character, the tone of his literary production.

Reasons for the trip

Here are two references about the decision to leave for such a distant and strange geography, inhospitable, in his health conditions, with adversities of all kinds, against medical indications and family pleas; to go to that cold Pacific island that required the immense crossing of Russian territory from east to west.

- Natalia Ginzburg in Anton Chekhov. Life through letters: “At the end of that year [1889], he accidentally read some notes from his brother Mijaíl, who was studying criminal law. He had the impression that people were interested in criminals until the day of sentencing, but that no one really knew how he lived in prisons or subjected to forced labor. He then had the idea of traveling to Siberia to learn about the life of the prisoners of the penal colony on the island of Sakhalin, located in the Pacific. He decided to leave for Sakhalin, despite the fact that all his family members begged him to give up the trip, fearing his fatigue and discomfort. Suvorin also tried to talk him out of leaving. It was all useless."

- Letter to Suvorin , the editor of Tiempo Nuevo and a close friend of his; March 9, 1890: “As for Sakhalin, we are both wrong, but perhaps you more than me. I leave with the absolute conviction that my trip will hardly contribute anything to literature or science; I lack, for this, the necessary knowledge, time and ambition. I don't have the plans of a Humboldt, not even a Kenan. I only want to write two or three hundred pages and thus pay off a debt I have contracted with medicine, with which, as you well know, I have behaved like a pig. I may not be able to write anything, but still the trip does not lose its attraction: reading, watching and listening, I will discover and learn many things. I haven't left yet, but thanks to the books I've had to read lately, I've learned a lot of things that everyone should know under penalty of forty lashes, and that I didn't know at all. Besides, I think that a six-month trip, with its uninterrupted physical and intellectual fatigue, will do me good, since I'm Ukrainian and I'm starting to get lazy. You have to tame nature itself. Let's admit that the trip is crazy, obstinate, extravagance, but think about it a bit and tell me what I'm losing: time? Money? Should fear of discomfort stop me? My time is worth nothing and I have never had money; As for the inconveniences, I will travel in carriages for twenty-five or thirty days at the most; the rest of the time I will spend on the deck of a steamer and bombard him with letters.”

Exit

Chekhov would be in Sakhalin for three months and three days. He would depart from Sakhalin to Moscow on October 13, making a crossing on the Petersburg steamer from Vladivostok (today the end point of the Trans-Siberian train that takes 7 days to reach Moscow; Japan was unfortunately closed due to a cholera epidemic), passing through Hong Kong. Kong, facing the China Sea -attacked by a typhoon-, Singapore and Ceylon en route to Odessa through the Indian Ocean, the Red Sea, the Suez Canal and the Black Sea. He was received by his family in Tula and from there he arrived in Moscow after almost eight months of intense and dangerous adventure.

And here begins the work that I am currently developing on Chekhov, life, art and death . I deliver this preview on the 162nd anniversary of his birth on January 29, 1860.

PS And since Chekhov loved music and used it frequently in his work, two versions of Kamarinskaya, composed by Mikhail Glinka in 1848, and which appears in a beautiful story by Anton, come to an end:

A. Version of the legendary Italian conductor Arturo Toscanini, which I like for its lively “tempo” contrasting with other symphonic versions:

B. And for those who prefer a short “popular” version, one with balalaika, by the Red Army musicians:

Hector Palacio on Twitter: @NietzscheAristo